By David Swanson, World BEYOND War, February 12, 2023

David Swanson is the author of the new book The Monroe Doctrine at 200 and What to Replace It With.

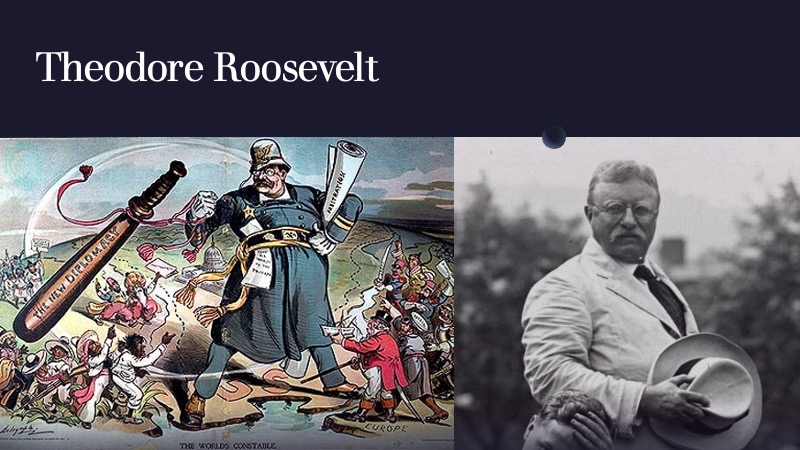

With the opening of the 20th century, the United States fought fewer battles in North America, but more in South and Central America. The mythical idea that a larger military prevents wars, rather than instigates them, often looks back to Theodore Roosevelt claiming that the United States would speak softly but carry a big stick — something that Vice President Roosevelt cited as an African proverb in a speech in 1901, four days before President William McKinley was killed, making Roosevelt president.

While it may be pleasant to imagine Roosevelt preventing wars by threatening with his stick, the reality is that he used the U.S. military for more than just show in Panama in 1901, Colombia in 1902, Honduras in 1903, the Dominican Republic in 1903, Syria in 1903, Abyssinia in 1903, Panama in 1903, the Dominican Republic in 1904, Morocco in 1904, Panama in 1904, Korea in 1904, Cuba in 1906, Honduras in 1907, and the Philippines throughout his presidency.

The 1920s and 1930s are remembered in U.S. history as a time of peace, or as a time too boring to remember at all. But the U.S. government and U.S. corporations were devouring Central America. United Fruit and other U.S. companies had acquired their own land, their own railways, their own mail and telegraph and telephone services, and their own politicians. Noted Eduardo Galeano: “in Honduras, a mule costs more than a deputy, and throughout Central America U.S. ambassadors do more presiding than presidents.” The United Fruit Company created its own ports, its own customs, and its own police. The dollar became the local currency. When a strike broke out in Colombia, police slaughtered banana workers, just as government thugs would do for U.S. companies in Colombia for many decades to come.

By the time Hoover was president, if not before, the U.S. government had generally caught on that people in Latin America understood the words “Monroe Doctrine” to mean Yankee imperialism. Hoover announced that the Monroe Doctrine did not justify military interventions. Hoover and then Franklin Roosevelt withdrew U.S. troops from Central America until they remained only in the Canal Zone. FDR said he would have a “good neighbor” policy.

By the 1950s the United States was not claiming to be a good neighbor, so much as the boss of the protection-against-communism service. After successfully creating a coup in Iran in 1953, the U.S. turned to Latin America. At the tenth Pan-America Conference in Caracas in 1954, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles supported the Monroe Doctrine and claimed falsely that Soviet communism was a threat to Guatemala. A coup followed. And more coups followed.

One doctrine heavily advanced by the Bill Clinton administration in the 1990s was that of “free trade” — free only if you’re not considering damage to the environment, workers’ rights, or independence from large multinational corporations. The United States wanted, and perhaps still wants, one big free trade agreement for all nations in the Americas except Cuba and perhaps others identified for exclusion. What it got in 1994 was NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement, binding the United States, Canada, and Mexico to its terms. This would be followed in 2004 by CAFTA-DR, the Central America – Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement among the United States, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, which would be followed by numerous other agreements and attempts at agreements, including the TPP, Trans-Pacific Partnership for nations bordering the Pacific, including in Latin America; thus far the TPP has been defeated by its unpopularity within the United States. George W. Bush proposed a Free Trade Area of the Americas at a Summit of the Americas in 2005, and saw it defeated by Venezuela, Argentina, and Brazil.

NAFTA and its children have brought big benefits to big corporations, including U.S. corporations moving production to Mexico and Central America in the hunt for lower wages, fewer workplace rights, and weaker environmental standards. They’ve created commercial ties, but not social or cultural ties.

In Honduras today, highly unpopular “zones of employment and economic development” are maintained by U.S. pressure but also by U.S.-based corporations suing the Honduran government under CAFTA. The result is a new form of filibustering or banana republic, in which the ultimate power rests with profiteers, the U.S. government largely but somewhat vaguely supports the pillaging, and the victims are mostly unseen and unimagined — or when they show up at the U.S. border are blamed. As shock doctrine implementers, the corporations governing “zones” of Honduras, outside of Honduran law, are able to impose laws ideal to their own profits — profits so excessive that they are easily able to pay U.S.-based think tanks to publish justifications as democracy for what is more or less democracy’s opposite.

David Swanson is the author of the new book The Monroe Doctrine at 200 and What to Replace It With.