By David Swanson, World BEYOND War, November 12, 2023

Remarks in Chicago on November 12, 2023

In the movie Good Morning, Vietnam the mean, ignorant superior officer tells the Robin Williams character:

“I got people stuck in places they haven’t even considered how to get out of yet. You don’t think I can come up with something good? Can you envision some fairly unattractive alternatives?”

And Robin Williams, without missing a beat, says “Not without slides.”

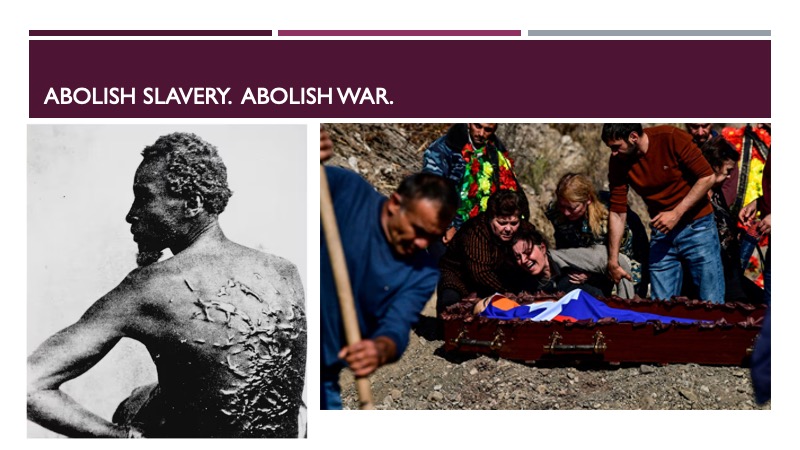

So, I’m going to try using slides here, as I’ve been asked to. I apologize if any of them are unpleasant. War is vicious and atrocious and our responsibility to abolish.

I’ve recently been told that people can’t understand what’s wrong with each separate war unless they go there. I recently watched an otherwise great interview of someone from the U.S. who said he didn’t understand Israeli apartheid until he went there. Not long ago I read a New York Times columnist practically bragging that he had denied climate change until somebody flew him to a glacier. This year a Russian columnist suggested using just one little nuclear weapon to teach people what it is so they wouldn’t use any. So, in the hope that we don’t actually have to fly every person to every spot on Earth, thereby achieving total death through jet fuel, or drop any bombs on ourselves as teaching aids, I am going to ask that you all try to make do with slides.

I secretly suspect that you wouldn’t even need slides if you didn’t have televisions and newspapers to try to overcome. I see polling that young people consume less media and that young people are smarter, for example in opposing at least certain wars. So, my hope is always to point people toward how to get information and understanding that is better than nothing, but even just nothing, for the average old person, can be a big step up.

The peace movement of the 1920s in the United States and Europe was larger, stronger, and more mainstream than ever before or since. In 1927-28 a hot-tempered Republican from Minnesota named Frank who privately cursed pacifists managed to persuade most countries on Earth to ban war. He had been moved to do so, against his will, by a global demand for peace and a U.S. partnership with France created through illegal diplomacy by peace activists. The driving force in achieving this historic breakthrough was a remarkably unified, strategic, and relentless U.S. peace movement with its strongest support in the Midwest; its strongest leaders professors, lawyers, and university presidents; its voices in Washington, D.C., those of Republican senators from Idaho and Kansas; its views welcomed and promoted by newspapers, churches, and women’s groups all over the country; and its determination unaltered by a decade of defeats and divisions.

The movement depended in large part on the new political power of female voters. The effort might have failed had Charles Lindbergh not flown an airplane across an ocean, or Henry Cabot Lodge not died, or had other efforts toward peace and disarmament not been dismal failures. But public pressure made this step, or something like it, almost inevitable. And when it succeeded — although the outlawing of war has never yet been fully implemented in accordance with the plans of its visionaries — much of the world believed war had been made illegal. Frank Kellogg got his name on the Kellogg-Briand Pact and a Nobel Peace Prize, his remains in the National Cathedral in Washington, and a major street in St. Paul, Minnesota, named for him — a street on which you cannot find a single person who doesn’t guess the street is named after a cereal company.

Wars were, in fact, halted and prevented. And when, nonetheless, wars continued and a second world war engulfed the globe, that catastrophe was followed by the trials of men accused of the brand new crime of making war, as well as by global adoption of the United Nations Charter, a document owing much to its prewar predecessor while still falling short of the ideals of what in the 1920s was called the Outlawry movement. In fact the Kellogg-Briand Pact had banned all war. The UN Charter legalized any war labeled defensive or authorized by the UN — making few if any wars legal, but allowing most people to falsely believe that most wars are legal.

Prior to Kellogg-Briand, war was legal, all wars, all sides of all wars. Atrocities committed during wars were almost always legal. The conquest of territory was legal. Burning and looting and pillaging were legal. The seizing of other nations as colonies was legal. The motivation for colonies to try to free themselves was weak because they were likely to be seized by some other nation if they broke free from their current oppressor. Economic sanctions by neutral nations were not legal, though joining in a war could be. And making trade agreements under the threat of war was perfectly legal and acceptable, as was starting another war if such a coerced agreement was violated. The year 1928 became the dividing line for determining which conquests were legal and which not. War became a crime, while economic sanctions became law enforcement. Conquest of territory dropped off by something like 99 percent.

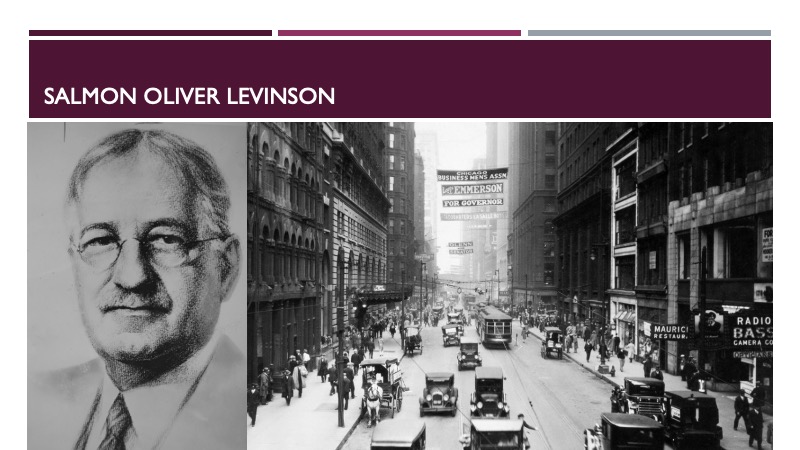

Frank Kellogg was dragged kicking and screaming to the strangest dream, to the agreement to put an end to war in a mighty room filled with men where the papers they were signing said they’d never fight again. He was dragged there by a wide and varied and international peace movement made up of dozens of diverse organizations and coalitions, a movement so divided that it negotiated compromises within itself. The idea that ended up achieving a ban on war came from the ubiquitous American Committee for the Outlawry of War, which was actually a front for a single individual and largely funded out of his own pocket. The American Committee for the Outlawry of War was the creation of Salmon Oliver Levinson. Its agenda originally attracted those advocates of peace who opposed U.S. entry into the League of Nations and international alliances. But its agenda of outlawing war eventually attracted the support of the entire peace movement when the Kellogg-Briand Pact became the unifying focus that had been missing.

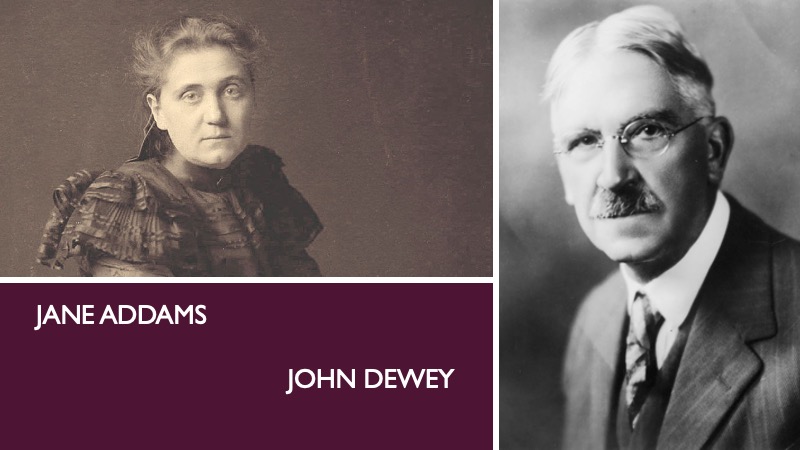

William James’ influence could be seen in Levinson’s thinking. Levinson also collaborated closely with the philosopher John Dewey, whom James had greatly influenced, as well as with Charles Clayton Morrison, editor of The Christian Century, and with Senator William Borah of Idaho, who would become Chair of the Committee on Foreign Relations just when he was needed there. Dewey had supported World War I and been criticized for it by Randolphe Bourne and Jane Addams, among others. Addams would also work with Levinson on Outlawry; they were both based in Chicago. It was the experience of World War I that brought Dewey around. Following the war, Dewey promoted peace education in schools and publicly lobbied for Outlawry. Dewey wrote this of Levinson:

There was stimulus — indeed, there was a kind of inspiration — in coming in contact with his abounding energy, which surpassed that of any single person I have ever known.

John Chalmers Vinson, in his 1957 book, William E. Borah and the Outlawry of War, refers to Levinson repeatedly as “the ubiquitous Levinson.” Levinson’s mission was to make war illegal. And under the influence of Borah and others he came to believe that the effective outlawing of war would require outlawing all war, not only without distinction between aggressive and defensive war, but also without distinction between aggressive war and war sanctioned by an international league as punishment for an aggressor nation. Levinson wrote,

Suppose this same distinction had been urged when the institution of duelling [sic] was outlawed. . . . Suppose it had then been urged that only ‘aggressive duelling’ should be outlawed and that ‘defensive duelling’ be left intact. . . . Such a suggestion relative to duelling would have been silly, but the analogy is perfectly sound. What we did was to outlaw the institution of duelling, a method theretofore recognized by law for the settlement of disputes of so-called honor.

Levinson wanted everyone to recognize war as an institution, as a tool that had been given acceptability and respectability as a means of settling disputes. He wanted international disputes to be settled in a court of law, and the institution of war to be rejected just as slavery had been.

Levinson understood this as leaving in place the right to self-defense but eliminating the need for the very concept of war. National self-defense would be the equivalent of killing an assailant in personal self-defense. Such personal self-defense, he noted, was no longer called “duelling.” But Levinson did not envision killing a war-making nation. Rather he proposed five responses to the launching of an attack: the appeal to good faith, the pressure of public opinion, the nonrecognition of gains, the use of force to punish individual warmakers, and the use of any means including force to halt the attack.

Of course we now know a great deal about the power of unarmed civilian defense, including that it works, and including that governments are afraid to train their own populations in it for obvious reasons, not because it doesn’t work.

World BEYOND War’s annual conference this year #NoWar2023 focused on this topic, and I recommend watching the videos.

Levinson came out of the Yale class of 1888, and went to work as a lawyer in Chicago. He believed reasonable lawyers could prevent trials. He later believed reasonable nations could prevent wars. Levinson became a skilled negotiator, a wealthy man, and the acquaintance of many wealthy and powerful people. He gave to all kinds of charities, including the peace movement.

When World War I started, Levinson organized influential people to present a peace plan to the German government. After the sinking of the Lusitania, Levinson — possibly ignorant of the Lusitania’s contents — asked Germany to “disavow” “war itself.” Levinson, of course, met with no success in his efforts to halt World War I. Yet this did not seem to discourage him in the least. It is unlikely that World War II or Korea or Vietnam or the Global War on (or is it of?) Terror or any of the current wars would have discouraged him either. Discouragement is something we impose on ourselves, and Levinson was not inclined in that direction.

Levinson began to see the central problem as war’s legality. He wrote on August 25, 1917: “War as an institution to ‘settle disputes’ and establish ‘justice among nations’ is the most barbarous and indefensible thing in civilization. . . . The real disease of the world is the legality and availability of war . . . . [W]e should have, not as now, laws of war, but laws against war; there are no laws of murdering or of poisoning, but laws against them.” Others had had a similar idea before, including slavery abolitionist Charles Sumner, who called both slavery and war “institutions,” but no one had ever made the idea widely known or built a campaign to realize its goals. Of course, now it’s been actively made so little known again that all kinds of people have the idea of banning war and propose it to me as a new idea, and when I tell them that it’s been banned and we have the much easier task of demanding compliance with the existing ban rather than having to create one from scratch and get war obsessed governments to join it, they lose some of their interest.

Early in the winter of 1917 Levinson showed a draft plan to outlaw war to John Dewey, who very much approved. Levinson published an article in The New Republic on March 9, 1918, in which he wrote of outlawing war. Levinson, in his early writings, quoted William James’ 1906 essay “The Moral Equivalent of War” which had included the line “I look forward to a future when acts of war shall be formally outlawed as between civilized people.” At first Levinson favored the League of Nations and an international court using force to impose its decisions, but he came to believe such “force” was just a euphemism for war, and that war could not be ended through war.

In June of 1918 Levinson was pleased to see Prime Minister of the United Kingdom David Lloyd George speak of “making sure that war shall henceforth be treated as a crime punishable by the law of nations.” Levinson at that time backed a strong League of Nations. He pitched both Outlawry and the League to peace groups including the League of Free Nations Association and the League to Enforce Peace. He organized mass meetings and other efforts, working with Jane Addams among others.

Levinson’s thinking, and consequently his political agenda, evolved during the decade of the search for peace. Charles Clayton Morrison’s book, The Outlawry of War, published with the close guidance of and dedicated to Levinson, crystallized the Outlawrists’ views in 1927. Dewey wrote the Foreword, in which he argued that Outlawry would allow internationalism without political entanglement with Europe, would end the divide between individual conscience and the rule of law (a divide created by the legal status of an enterprise of mass killing), and would complete a process from barbarism to civility that had already put an end to private blood feuds and dueling. Dewey suggested that the legal status of war allowed the threat of war to facilitate the economic exploitation of weaker countries. Dewey, who was early to recognize the impact on world affairs of the combination of “the checkbook and the cruise missile” (the title of a 2004 book by Arundhati Roy), envisioned a truly new world that would be produced by banning war and eliminating the threat of it.

The peace movement that grew during the 1920s developed in a nation different from the United States of the twenty-first century in many ways. One of them was the state of political parties. The Republicans and Democrats were not the only game in town. They were pushed in the direction of peace and social justice by the Socialist and Progressive Parties. By 1912, the Socialist Party had elected 34 mayors and numerous city councilors, school board members, and other officials in 169 cities nationwide. In some states, the Socialist Party held the second highest number of seats in the legislature. The first Socialist was elected to Congress in 1911. By 1927, there would be one Socialist and three Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party members in Congress, along with a slim Republican majority in the Senate and a large Republican majority in the House.

All four parties were brought to support the abolition of war. Any civic group in the United States that has been around for 100 years, any religious denomination, the League of Women Voters, the American Legion, they are all on record supporting the banning of all war. To my knowledge none of them have ever renounced it; they’ve just survived into an era when nobody can even imagine it. The platform of the Progressive Party said, “We favor an active foreign policy to bring about a revision of the Versailles Treaty in accordance with the terms of the armistice, and to promote firm treaty agreements with all nations to outlaw wars, abolish conscription, drastically reduce land, air, and naval armaments, and guarantee public referendum on peace and war.”

Did banning war do any good? It used to be legal. Now it’s illegal but everybody thinks it’s legal. Either way it’s mass murder and massive destruction. Anyone who has even heard of the Kellogg-Briand Pact at all has heard the same one thing about it: it didn’t work because World War II happened. I have a few responses to that.

1) Banning law was supposed to be a step toward a culture that shunned war. Lots of human societies have lived without war and found the idea revolting. Making war a crime is a useful step in that direction.

2) If you’re going to make something a crime, you have to prosecute it. There has to be some system of punishment or reparation, restitution, or reconciliation. Very few wars have been punished at all. They’ve only been punished by the victors against the losers. They’ve not been punished as wars but as particular atrocities within wars. The trials of individuals by the International Criminal Court do not touch the big war makers who have UN veto power. While the Pact was the basis for Nuremberg and Tokyo, one-sided justice is not justice. While the ICC at long last claims it will prosecute war, it calls it “aggression,” meaning that it will be one-sided, and it has yet to do so at all.

3) Murder and rape and theft and other crimes have been on the books for thousands of years and continue, and virtually nobody declares the laws against them to have not worked and therefore the answer is to toss out the laws and go on murder-rape-and-theft sprees. Some point to the failure of laws, but always to improve them, not to toss them out entirely upon their very first application. If the first drunk driving incident following the banning of driving drunk had resulted in tossing out the law as a failure, people would have called that crazy. If the first prosecution had resulted in no more drunk driving, people would have called that miraculous. Yet after one biased and distorted application of the Kellogg-Briand Pact after World War II, the big militaries have not gone to war against each other again yet. They’ve waged wars on and through smaller nations instead — the equivalent perhaps of bicycling drunk. Is that because they have nuclear weapons? It’s probably because of a lot of things. One of them is an idea that still excites sane people and frightens war profiteers, the idea of leaving war behind us.

Of course, banning war while manufacturing weapons and plotting wars and inflicting suffering that breeds a desire for vengeance may not eliminate war. But what if we could move our culture toward a place where governments attempted respect and honesty, where so-called representatives tried to represent public wishes, where international institutions were democratized, and the the rule of law was applied equally, rather than as a club with which the Rules Based Order can rule through violence.

One step toward such a culture is honoring the steps that have brought us this far. In 2015, in Chicago, David Karcher and Frank Goetz and the staff at Oak Woods Cemetery managed to locate the grave of Salmon Oliver Levinson. Every child in Chicago should know it.

Why does war keep happening?

It’s been normalized through the biggest and longest propaganda campaign ever run. People believe, absurdly, that war can bring peace, that war can bring justice, that war can prevent something worse than war, that war is inevitable so you might as well win it, that investing in war like only this 4% of humanity does is simply the unavoidable behavior of all humans, that the other 96% of humanity is even worse and incapable of rational thought thus able to understand only war, that wars can be won, that wars can be fought properly and cleanly and humanely, that war is a public service that good global citizens should provide the the greatest extent that they can afford even if it means starving their people, and that we should always spend a good deal of time slowly discovering that each new war is unjust and fraudulent but be prepared to fall for some wars, and not others, depending on the type and the details.

Since I think people care about what they see, and since we’ve seen what the Black Lives Matter movement has done with videos and photos, I want to demonstrate my answer to the question “What should we do?” by showing you some slides.

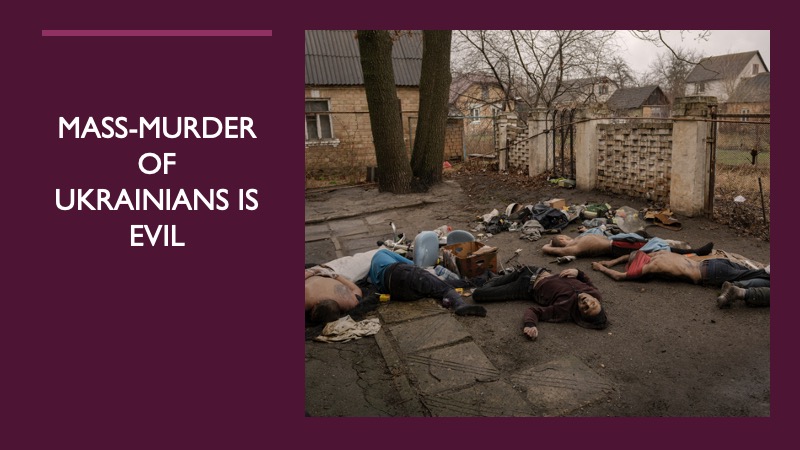

These are Ukrainians.

These are Russians.

These are Israelis.

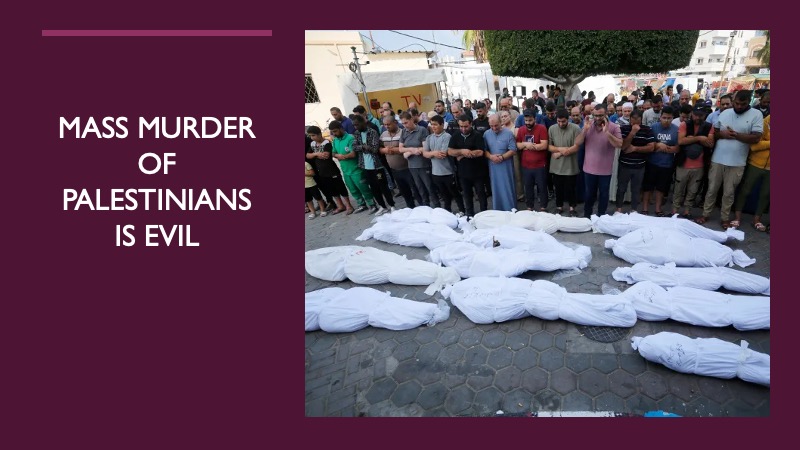

These are Palestinians.

These are all the people it’s OK to murder.

It’s easy to get discouraged as old crusty warmongers you thought had died when you were a kid are wheeled out to comment on and profit from each war, and as identity politics is further entrenched through war support and opposition alike.

And yet

And yet, people, lots and lots of people, those qualified by having just stumbled out of the rubble in Israel, and otherwise — masses of people — people risking arrest, people turning out in the streets just as people do in normal countries, people surrounding the White House and the Capitol, crowds of diverse and heartwarming people have been getting and saying and doing everything exactly right.

Horribly insufficient as the response has been to a publicly celebrated genocide in Gaza, it has not been, in the United States, as bad as the response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. So, in the words of the late — I mean, oh god he’s still with us — George W. Bush, is our children learning?

Maybe. Maybe. The question I want to answer is whether anyone is following the logic of opposing both sides to where it leads. If you’ve understood that denouncing the mass slaughter of civilians by two sides of a war is not only the right thing to say but honestly the right thing to believe, and if you’ve exclaimed that “It’s not a war, it’s something worse” but also noticed that we’ve been exclaiming that during just about every war since World War I, then do you follow the logic where it leads? If both sides are engaged in immoral outrages, if the problem is not whichever side you’ve been trained to hate, but war itself. And if war itself is the biggest drain on resources desperately needed thereby killing more people indirectly than directly, and if war itself is the reason we are at risk of nuclear Armageddon, and if war itself is a leading cause of bigotry, and the sole justification for government secrecy, and a major cause of environmental destruction, and the big impediment to global cooperation, and if you’ve understood that governments do not train their populations in unarmed civilian defense not because it doesn’t work as well as militarism but because they are afraid of their own populations, then you are now a war abolitionist, and it’s time we set to work, not saving our weapons for a more proper war, not arming the world to protect us from one club of oligarchs getting richer than another club of oligarchs, but ridding the world of wars, war plans, war tools, and war thinking.

Goodbye, war. Good riddance.

Let’s try peace.

We should try holding people accountable despite their positions of power. One effort to do that begins this evening at 7 p.m. Central Time at MerchantsOfDeath.org Please watch it.

I want to save a lot of time for questions. But I want to say something about yesterday, about what so many people in the United States call Veterans’ Day.

Kurt Vonnegut once wrote: “Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans’ Day is not. So I will throw Veterans’ Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don’t want to throw away any sacred things.” Vonnegut meant by “sacred” wonderful, valuable, worth treasuring. He listed Romeo and Juliet and music as “sacred” things.

Exactly at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, in 1918, 100 years ago this coming November 11th, people across Europe suddenly stopped shooting guns at each other. Up until that moment, they were killing and taking bullets, falling and screaming, moaning and dying, from bullets and from poison gas. And then they stopped, at 11:00 in the morning, one century ago. They stopped, on schedule. It wasn’t that they’d gotten tired or come to their senses. Both before and after 11 o’clock they were simply following orders. The Armistice agreement that ended World War I had set 11 o’clock as quitting time, a decision that allowed 11,000 more men to be killed in the 6 hours between the agreement and the appointed hour.

But that hour in subsequent years, that moment of an ending of a war that was supposed to end all war, that moment that had kicked off a world-wide celebration of joy and of the restoration of some semblance of sanity, became a time of silence, of bell ringing, of remembering, and of dedicating oneself to actually ending all war. That was what Armistice Day was. It was not a celebration of war or of those who participate in war, but of the moment a war had ended.

Congress passed an Armistice Day resolution in 1926 calling for “exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding … inviting the people of the United States to observe the day in schools and churches with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.” Later, Congress added that November 11th was to be “a day dedicated to the cause of world peace.”

We don’t have so many holidays dedicated to peace that we can afford to spare one. If the United States were compelled to scrap a war holiday, it would have dozens to choose from, but peace holidays don’t just grow on trees. Mother’s Day has been drained of its original meaning. Martin Luther King Day has been shaped around a caricature that omits all advocacy for peace. Armistice Day, however, is making a comeback.

Armistice Day, as a day to oppose war, had lasted in the United States up through the 1950s and even longer in some other countries under the name Remembrance Day. It was only after the United States had nuked Japan, destroyed Korea, begun a Cold War, created the CIA, and established a permanent military industrial complex with major permanent bases around the globe, that the U.S. government renamed Armistice Day as Veterans Day on June 1, 1954.

Veterans Day is no longer, for most people, a day to cheer the ending of war or even to aspire to its abolition. Veterans Day is not even a day on which to mourn the dead or to question why suicide is the top killer of U.S. troops or why so many veterans have no houses. Veterans Day is not generally advertised as a pro-war celebration. But chapters of Veterans For Peace are banned in some small and major cities, year after year, from participating in Veterans Day parades, on the grounds that they oppose war. Veterans Day parades and events in many cities praise war, and virtually all praise participation in war. Almost all Veterans Day events are nationalistic. Few promote “friendly relations with all other peoples” or work toward the establishment of “world peace.”

In fact, then-President Donald Trump tried unsuccessfully to hold a big weapons parade in the streets of Washington, D.C., on so-called Veterans Day — a proposal happily canceled after it was met by opposition and almost no enthusiasm from the public, media, or military.

Veterans For Peace, on whose advisory board I serve, and World BEYOND War, which I am the director of, are two organizations promoting the restoration of Armistice Day.

In a culture in which presidents and television networks lack the subtlety of a show-and-tell event in a preschool, it is perhaps worth pointing out that rejecting a day of celebrating veterans is not the same thing as creating a day for hating veterans. It is in fact, as proposed here, a means of restoring a day for celebrating peace. Friends of mine in Veterans For Peace have argued for decades that the best way to serve veterans would be to cease creating more of them.

That cause, of ceasing to create more veterans, is impeded by the propaganda of troopism, by the contention that one can and must “support the troops” — which usually means support the wars, but which can conveniently mean nothing at all when any objection is raised to its usual meaning.

What’s needed, of course, is to respect and love everyone, troops or otherwise, but to cease describing participation in mass killing — which endangers us, impoverishes us, destroys the natural environment, erodes our liberties, promotes xenophobia and racism and bigotry, risks nuclear holocaust, and weakens the rule of law — as some kind of “service.” Participation in war should be mourned or regretted, not appreciated.

The largest number of those who “give their lives for their country” today in the United States do so through suicide. The Veterans Administration has said for decades that the single best predictor of suicide is combat guilt. You won’t see that advertised in many Veterans Day Parades. But it is something understood by the growing movement to abolish the entire institution of war.

World War I, the Great War (which I take to have been great in approximately the Make America Great Again sense), was the last war in which some of the ways people still talk and think about war were actually true. The killing took place largely on battlefields. The dead outnumbered the wounded. The military casualties outnumbered the civilians. The two sides were not, for the most part, armed by the very same weapons companies. War was legal. And lots of really smart people believed the war lies sincerely and then changed their minds. All of that is gone with the wind, whether we care to admit it or not.

War is now one-sided slaughter, mostly from the air, blatantly illegal, no battlefields in sight — only houses. The wounded outnumber the dead, but no cures have been developed for the mental wounds. The places where the weapons are made and the places where the wars are waged have little overlap. Many wars have U.S. weapons — and some have U.S.-trained fighters — on multiple sides. The vast majority of the dead and wounded are civilian, as are the traumatized and those made homeless. And the rhetoric used to promote each war is as worn thin as the 100-year-old claim that war can put an end to war. Peace can put an end to war, but only if we value and celebrate it.

On December 2, 1920, Al Jolson wrote a letter to President-Elect Warren Harding. It read:

Take away the gun

From ev-ry mother’s son.

We’re taught by God above

To forgive, forget and love,

The weary world is waiting for,

Peace, forevermore,

So take away the gun

From ev-ry mother’s son,

And put an end to war.